Now that my year-long dive into hour-long introductory playlists is finally over, I thought I would try something a little different. Going back to my last subject before 2020, I’m looking again at the Beatles.

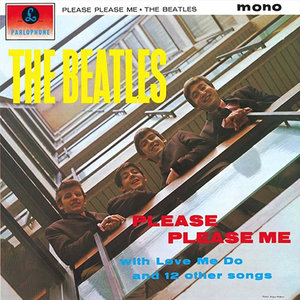

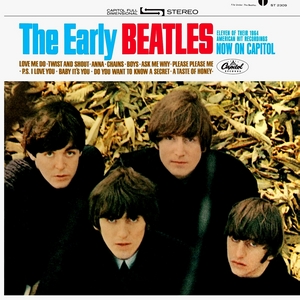

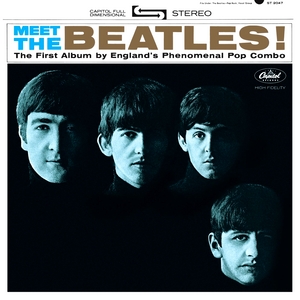

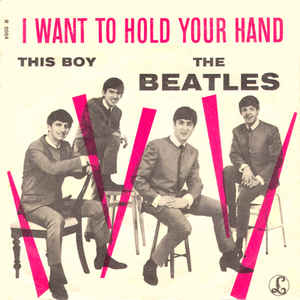

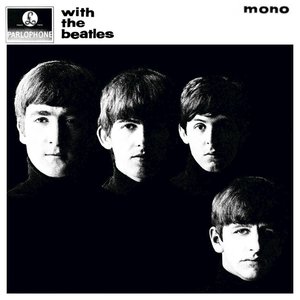

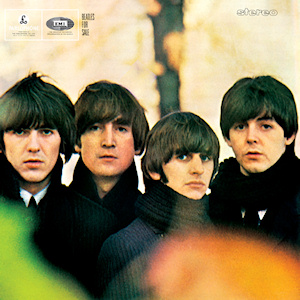

During the early years of the Beatles (1962 – 1966, the “Red” album years), the band would meticulously craft stellar pop albums for Parlophone, the UK record label. Parlophone was a subsidiary of EMI – whose American counterpart, Capital Records, didn’t even want to release the Beatles records in the USA letting tiny labels like Swan and VeeJay have the first crack at them. By the time of the Ed Sullivan Show and the Can’t Buy Me Love and the whole Beatlemania thing, Capital were finally on-board, but they didn’t have to put out the albums exactly as the Beatles and EMI did.

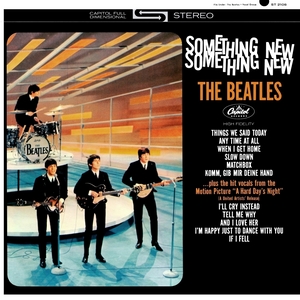

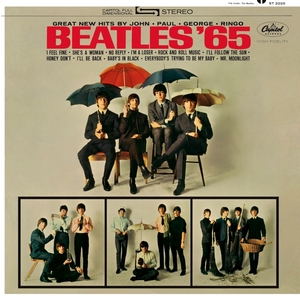

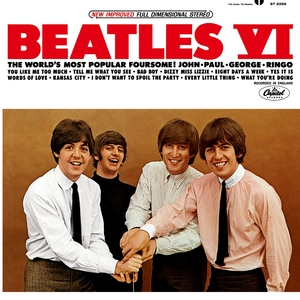

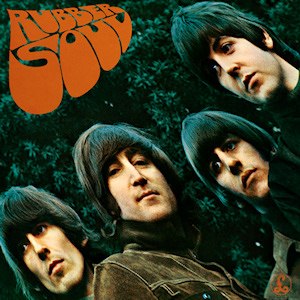

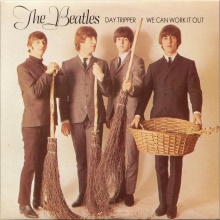

In England, Beatles albums usually had fourteen songs, and the singles released were not found on the album to give the consumer the most band for their buck (or pound). In America, the accountants knew that they could thin out the supply a bit to get more return on their investment. Therefore, most American albums by the Beatles only had eleven or twelve tracks and usually would include the singles on there. By using this practice, Capital could turn the first seven albums into a total of eleven.

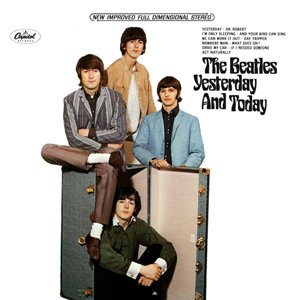

The band itself were none to happy with this practice. It not only felt like a rip-off to their fans, but also messed with their artistic vision. When Capitol needed a new cover for the totally made up Yesterday… and Today album, John Paul, George, and Ringo submitted the infamous “butcher cover” replete with slabs of meat and bloody doll heads to express their displeasure. Starting with Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band, the Beatles used their considerable weight to force Capitol to start releasing the albums the same way as their British counterparts. Once the Beatles catalog was released on CD in 1987, the UK versions were used as the template (with one exception) and that is the way the Beatles albums have been really seen and dealt with ever since.

But what if Capitol had refused to comply in 1967? What would subsequent Beatles releases look like? They certainly wouldn’t be better. While some may stick up for the occasional US tracklist, most people agree that the UK version is closer to what the Beatles intended and therefore is superior. So this hypothetical exercise isn’t about making the Beatles music better (if that’s even possible), but is just an excuse to dive deep into the catalog and think about all these great songs again.

I figured this would mostly be an excuse to really concentrate on the “Blue Album” years, but before I could really dive in, I had to seriously study the American albums and try to figure out what (if anything) Capitol was thinking and how they tried to chop these LPs up in order to squeeze as many golden eggs as they could from these crazy goose. So in fact I really got to know the early years a lot better than I expected.

Looking and and comparing the US vs UK albums, here is what I found:

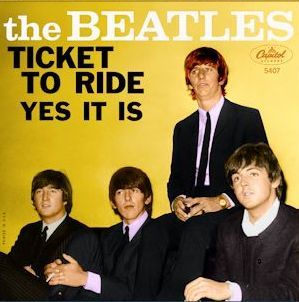

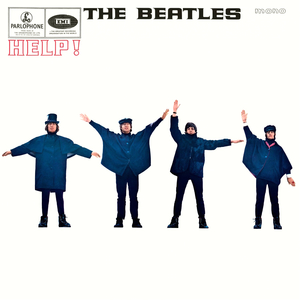

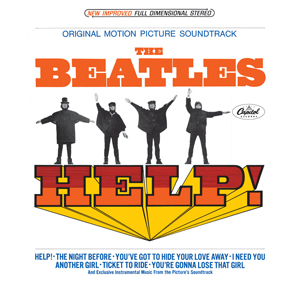

The first seven UK albums came out every 205 days approximately, consisted of 14 songs apiece and were a little over thirty-three minutes in length on average. The first 11 American albums came out every 93 days, with an average of 11.3636 songs per album and a length of twenty-seven minutes and twenty-one seconds. Here is a run-down of the releases on the different sides of the pond. Some things to note: the two soundtrack albums, A Hard Day’s Night and Help! were technically released on United Artists and not Capitol. They included a few non-Beatles songs from the actual soundtrack of the film to help pad out the albums more and spread out the songs. Also, they didn’t include any songs that were not actually used within the film itself. This is good information to know when constructing new versions of Magical Mystery Tour, Yellow Submarine, and Let It Be. Also, on a few occasions, the same song did appear on two albums, mostly because Capitol and United Artists both wanted to use the same hit. I tried to avoid doing this with my new hypothetical US albums, but it is nice to know. Also, the release of Komm Gib Mir Deine Hand on Something New seems to indicate that they were willing to use just about anything to fill up the quota for an album.

Using this information, and the patterns I can detect, I will now try to reconfigure Sgt. Pepper through Abbey Road into Capitol’s ideal method of capitalizing on the Beatles.